Too much of a good thing

Too much of a good thing

Urban Capital is an urban regenerator. From its start in Toronto’s King-Spadina district in the late 1990s, it has tried to be at the vanguard of urban change. But there’s a flip side of this—“gentrification”, where people get displaced. When does too much of a good thing—regeneration—become a bad thing—gentrification? Brandon Donnelly looks for the answer, and asks what can be done to offset the negative impacts of urban regeneration.

The 1960s through to the 1980s were not kind to many cities in North America, Europe and the UK. The economy was going through a process of industrial restructuring. Racial tensions were high, particularly in the US. And the lure of the suburb proved irresistible to an auto-oriented generation who saw cities as blighted and dangerous.

In 1967, Detroit saw one of the most destructive riots in the history of the United States. It lasted five days and resulted in 43 deaths and the destruction of over 2,000 buildings. From 1960 to 1980 the city lost nearly 30% of its population–a decline that continued into the 21st century and has only recently been reversed.

On October 16, 1975, New York City was less than 24 hours from declaring bankruptcy, as $350 million of debt was about to come due. The economic fallout from deindustrialization had hit the city hard and crime had risen dramatically. By the end of the decade the city would lose nearly a million people and then see the start of what became known as the “crack epidemic.” People avoided “the city” – the city being Manhattan. It was simply too dangerous.

Cities, it would seem, were dying

Yet despite this dire urban backdrop, concerns over gentrification were not non-existent. New York neighbourhoods such as the South Houston Industrial District (today’s SoHo) and the Lower East Side were embroiled in fights over highways, displacement, and gentrification throughout the 1960s, 70s, and 80s.

Indeed, the term “gentrification” can be traced back to 1964, when it was coined by the German-born British sociologist Ruth Glass. She described it as a rapid process where modest mews, cottages, and previously subdivided Victorian houses were upgraded to elegant and expensive houses – ultimately upsetting the whole social order of the district.

Baron Haussmann – the original gentrifier

Even before the term had been coined, “gentrification” as an urban phenomenon had long entered the mind of city dwellers. From the 1850s to the 1870s, during Baron Haussmann’s complete destruction of working-class medieval Paris, the French poet Charles Baudelaire wrote about the estrangement he felt with this newer and richer Paris. This was 19th century gentrification at work.

But is gentrification always a bad thing? As Detroit bled people in the post-war years, would anyone have opposed a new “luxury” condo tower, assuming it could have been built? Should Haussmann and Emperor Napoléon III have left Paris the way it was? The generation that was displaced wasn’t all that thrilled, but today Paris is one of the most admired and visited cities in the world. So was it worth it?

De-gentrification is not a great alternative

Another way to look at gentrification is that it by definition requires capital investment. To renovate and regenerate a neighbourhood is to invest money and make new things. Therefore, the opposite of gentrification – let’s call it de-gentrification – would be disinvestment. This is where capital investments are not made. Things are left to age, because let’s keep in mind that all built form depreciates over time. Nothing is static.

Most people would probably agree that disinvestment is not an optimal outcome for communities. And you don’t have to look hard to find examples of it. In 1970, the United States had 1,100 urban Census tracts that could be classified as “high poverty.” By 2010, 40 years later, that number had climbed to 3,165. This is disinvestment. This is the lack of gentrification, which doesn’t always get talked about.

Developers such as Urban Capital have positioned themselves as urban regenerators. What started with a late 1990s boutique loft project – Camden Lofts – in Toronto’s hollowed out Fashion District has grown into a firm philosophy around investing in and regenerating neglected urban areas. In 2013 the company completed the first phase of its four-phase River City development. It was the first building in Toronto’s emerging West Don Lands district, previously a derelict area completely outside the consciousness of Torontonians.

The corner of Bank and McLeod, Ottawa, before and after Central Phase 1. The three phase Central development replaced the vacant Metropolitan Bible Church and two surface parking lots with 525 condominium units, stitching together the urban fabric on this stretch of Bank Street, but unleashing a firestorm of protest against the “gentrification” of the neighbourhood.

Earlier, with its East Market development in 2001, Urban Capital kickstarted what ultimately grew into quite a condo boom in Ottawa. East Market was at the scruffy end of the city’s Byward Marke on a one-acre empty parking lot adjacent to a Salvation Army hostel. It was the first major condominium development proposed in the city’s central district in over ten years.

And today, with the completion of its Glasshouse condominium in Winnipeg, Urban Capital is delivering 200 new residential units in a downtown bereft of permanent residents.

Wake up and smell the gentrification

But at what point does urban regeneration become unwanted gentrification?

In 2012, on the heels of its successful East Market and then Mondrian developments, Urban Capital returned to Ottawa to launch an infill project in an area of the city that it felt represented an urban void between the downtown core and the trendy Glebe neighbourhood. UC’s objective was to re-energize a stretch of blocks that was, at the time, characterized by a mostly surface parking lots.

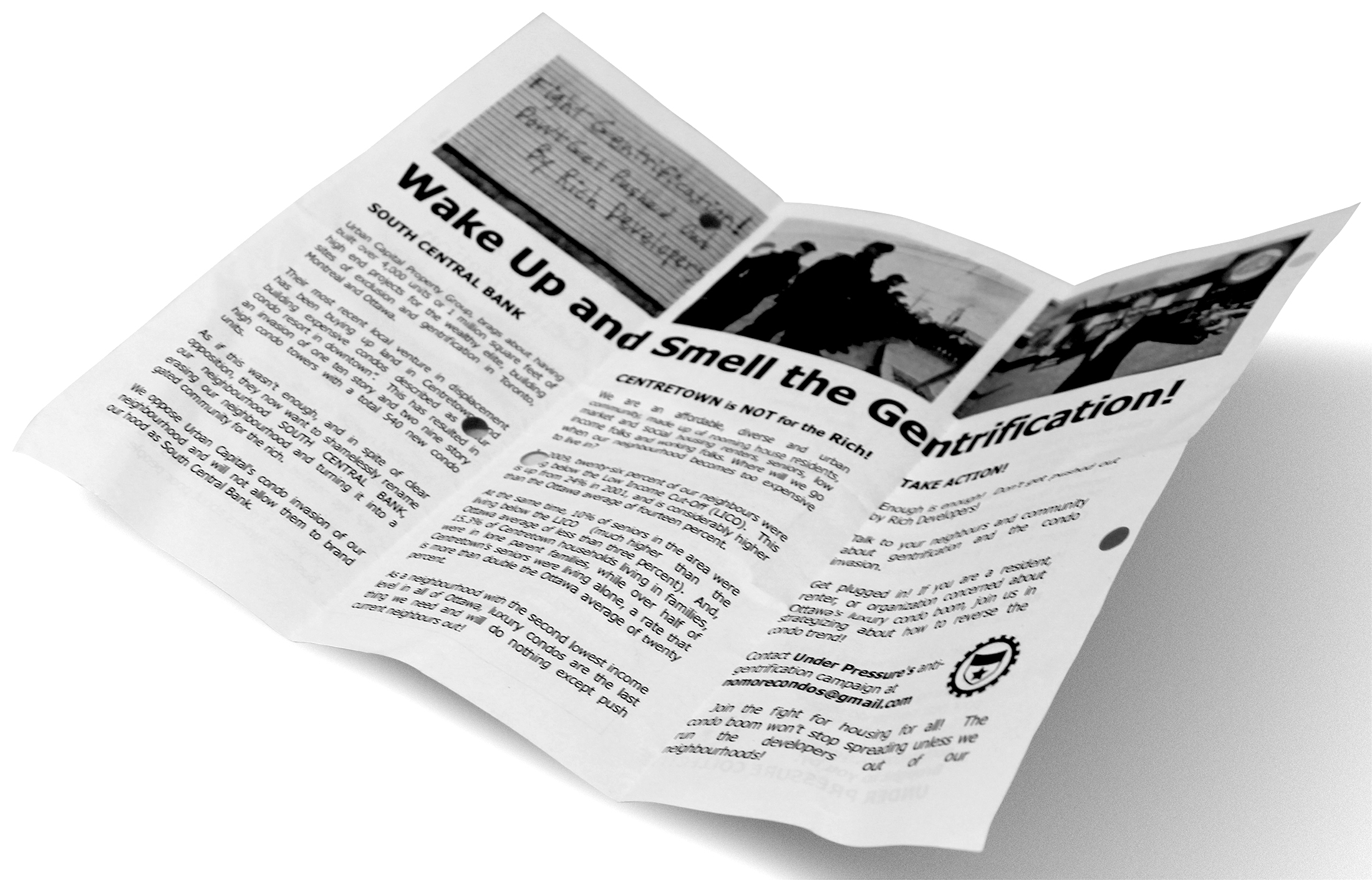

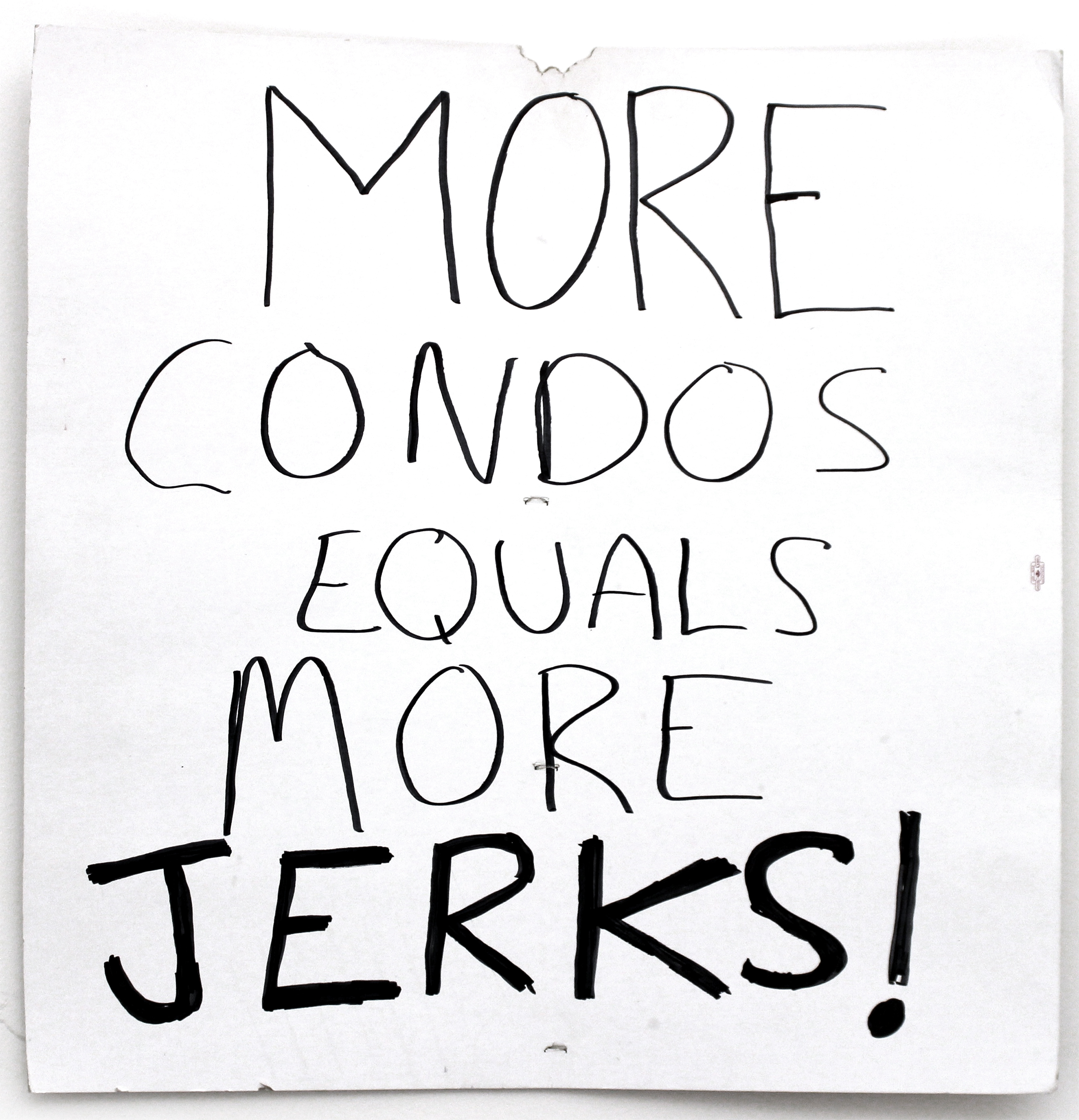

However, instead of being welcomed as an urban regenerator, as it had been with East Market and other projects, the company was seen as an intruder coming in to build luxury condos for the wealthy. An anti-gentrification campaign quickly emerged with flyers screaming: “Wake Up and Smell the Gentrification!” The gist of their strongly rhetorical message: Don’t get pushed out by rich developers.

Of course, this is not unique to Urban Capital in Ottawa. Gentrification battles and fears of displacement dominate headlines around the world. In many ways it is symptomatic of a larger socioeconomic shift: income inequality is rising and the middle class is being squeezed out. The results of this now play out on our streets with every new condo development and hipster coffee shop.

Good at the beginning; not so good later on

Perhaps the main difference between welcome regeneration and unwanted gentrification is that the revitalization of neglected urban areas —the “welcome regeneration”— often does not directly impact that many people.

There’s nobody there to oppose change at the beginning. Things are just getting starting. For instance, no one lived in Toronto’s Fashion District in the 1990s, and most people did not believe that this de-industrialized part of the city would one day be transformed into the thriving mixed-use community that it is today. So urban regeneration was not only not opposed, it was actively encouraged.

But as communities mature and people begin to fear that additional investment will translate into displacement and/or a reduction (or even change) in their quality of life, NIMBYism takes root. Urban Capital has projects from the Maritimes to the Prairies, and partner David Wex describes the evolution this way: “I’m usually pretty popular at the start of a city’s upswing, and then disdained (at best) later on.”

It would seem that cities only have two states: they’re either on the brink of death or they’re being gentrified and over-developed by nasty developers.

West Don Lands, before and after the River City Phase 1 and 2 redevelopment. River City replaced a post-industrial wasteland, so there was no immediate local community to decry “gentrification”.

Inclusive urbanism

It is short-sighted to think that as cities and neighbourhoods cross the chasm from under-the-radar regeneration to unwanted gentrification, simply stopping change will preserve the status quo. Instead, we must find the right balance between growth and preservation. And we need to get better at creating inclusive urbanism.

Earlier this year, at the 24th Annual Congress for the New Urbanism in Detroit, Carol Coletta of the Kresge Foundation’s American Cities practice delivered a keynote speech where she spoke about the transforming city and the battles of gentrification. She urged everyone to consider the value of mixed-income communities, and gentrification – without displacement. She ended by saying: “Equity does not sit in opposition to a thriving, appealing city. It is central to it.”

Since the very beginning, people have moved to cities in search of social interaction and wealth creation. So it strikes me that the concern may not necessarily be that neighbourhoods could be becoming wealthier (gentrified), but rather that the investments being made and the benefits being created are not being broadly shared. And that some people are not only being left out, but are in fact getting pushed out.

So what should we do? First, we shouldn’t assume that this is entirely a design, real estate and city planning problem. Exponential technological growth has caused rapid structural changes in our economy, manifesting itself in an economic “decoupling”. This has been well documented. A 2012 study by Andrew McAfee, a research scientist at MIT, found that while U.S. productivity and GDP have continued to grow since the early 1980s, median household income has in fact decreased. This is the hollowing out of the middle class that is driving the populism – in Europe as well as the U.S. – that we are seeing today. Sadly, this is not a problem that architects and real estate developers, alone, can solve.

Second, we – meaning everyone involved in the built environment – need to do more to create inclusive urbanism. This means mixed-income and mixed-use communities that minimize displacement and ensure that residents are well connected to jobs, education, and other services. Already, cities such as Toronto have by-laws in place to preserve affordable and mid-range rental housing in the face of new development. Residential rents are also controlled, with maximum annual increases set by the government. You could call these anti-displacement policies.

Third, there has been much debate about the connection between new housing supply and affordability. On one side you have Harvard economist Edward Glaeser, who touts the affordability success of cities such as Houston, a sprawling metropolis with few land use controls. And on the other you have people like urbanist Richard Florida, who have become frustrated with this proposed solution to inclusivity.

It is unlikely that supply alone will solve the urban affordability crisis, but there is a clear connection. Heavily supply constrained cities – Vancouver because of its hemmed-in geography, and Toronto (arguably) because of its greenbelt – have seen prices increase faster than more elastic markets. That’s because the rich will always outbid the poor for housing – particularly when supply is fixed. So stopping new supply does not guarantee that displacement will not happen. In fact, it may even exacerbate it. For without new supply, the wealthy will simply look to gentrify the existing housing stock.

Vital cities evolve

As counterintuitive as some of this may seem at first, investment in cities is a sign of vitality. Every construction crane or sidewalk repair is money being spent to maintain and, hopefully, improve the environment in which we live. When cities and neighbourhoods fall into neglect, we seem to be able to recognize the value of change. That’s when we invite urban regeneration. That’s when we want to see that crane up in the sky. But at some point there’s a feeling – and it’s not a new feeling, as evidenced by the “Haussmannization” of Paris – that it’s simply too much of a good thing. Enough is enough.

Not all development is good development, but we must find a balance. Cites are incredibly powerful and resilient organisms. They welcome us in. They allow us to live our lives with our families and friends. And they empower us to generate wealth. But in order for them to do that best, they need to be allowed to adjust, evolve, and grow.

Rather than try and stop urban change, a more productive set of questions would be: Are we using this opportunity to improve the built environment and create inclusive urbanism? And how can we ensure that the benefits will be more broadly shared? These are the great challenges facing our cities today.

And if we don’t address them head-on, the gentrification battles will only get nastier. UC